A Life Committed to Outward Bound

Stowed away in his grandmother’s old and weathered steamer trunk survived tattered letters, faded photographs, military records and treasured mementos from a life impassioned and transformed by Outward Bound. A letter addressed to Mom and Dad read, “As with the fellows I’m with…I’ve never worked with a greater bunch…P.S. the food is terrific…[and] is no doubt a morale factor.” Signed and dated, Chris, Aug. 30, 1967.

Chris Robbins carried this enthusiasm from his first seafaring program in the summer of 1967, aboard H-8 – a 25-day adult “instructor” course intended for educators and professionals interested in bringing Outward Bound principles back to their home organizations. Working at the Harvey School outside of New York City, Robbins planned to bring a wilderness elective program with ropes challenge elements back to his students.

The trunk was a time capsule of sorts, relics of a former life and career trajectory that would evolve into a half century of Outward Bound history and influence. Robbins shares a story from course of a crewmate insisting to be tied to the mast, like Ulysses in search of the sirens’ song. The crew obliged and covered their ears on command while he serenaded the ship. Robbins’ amusement of the absurd scene evokes a more profound and symbolic memory of brotherhood, courage, and leadership that will no doubt steer him in the years to come.

Robbins fondly recalls his mentorship under instructor, Will Lange: “It’s very humbling, but you know you’re in safe hands. You’ve got a role and your instructor says you’ve got to get from point A to point B with these strangers.” One particularly foggy day, Robbins remembers his crew rowed tirelessly for 30 straight minutes before the demoralizing realization set in that they hadn’t covered any ground. Lost without bearings in an expanse of pea soup, their synchronized stokes battled a fierce and mighty riptide. Together, they relied upon their combined strength and skills to adapt and navigate the unfamiliar and unrelenting landscape of the open ocean.

Robbins’ crewmates came from a variety of institutions and backgrounds and looked to Lange for instruction on integration and application of Outward Bound principals into their respective programs and curriculum back home. The lessons proved universal and applicable across the diverse crew. Robbins reflects, “Will [Lange] was an expert at that.” Lange, who went on to direct the Dartmouth College Outward Bound Center, proved to Robbins the adaptability of the Outward Bound ethos for any number of populations and outcomes, from adjudicated youth services, to Ivy League scholars, to professional educators, and to young adolescents maturing into leaders of character.

Lange later convinced Robbins to return to Hurricane Island as an assistant instructor in the summers following his initial course, further establishing his Outward Bound edification. After just his second summer of instructing in 1969, Robbins was drafted into the military, at the height of the Vietnam War. Robbins spent 3 years on active duty, and then served 18 years in the Army Reserves and National Guard.

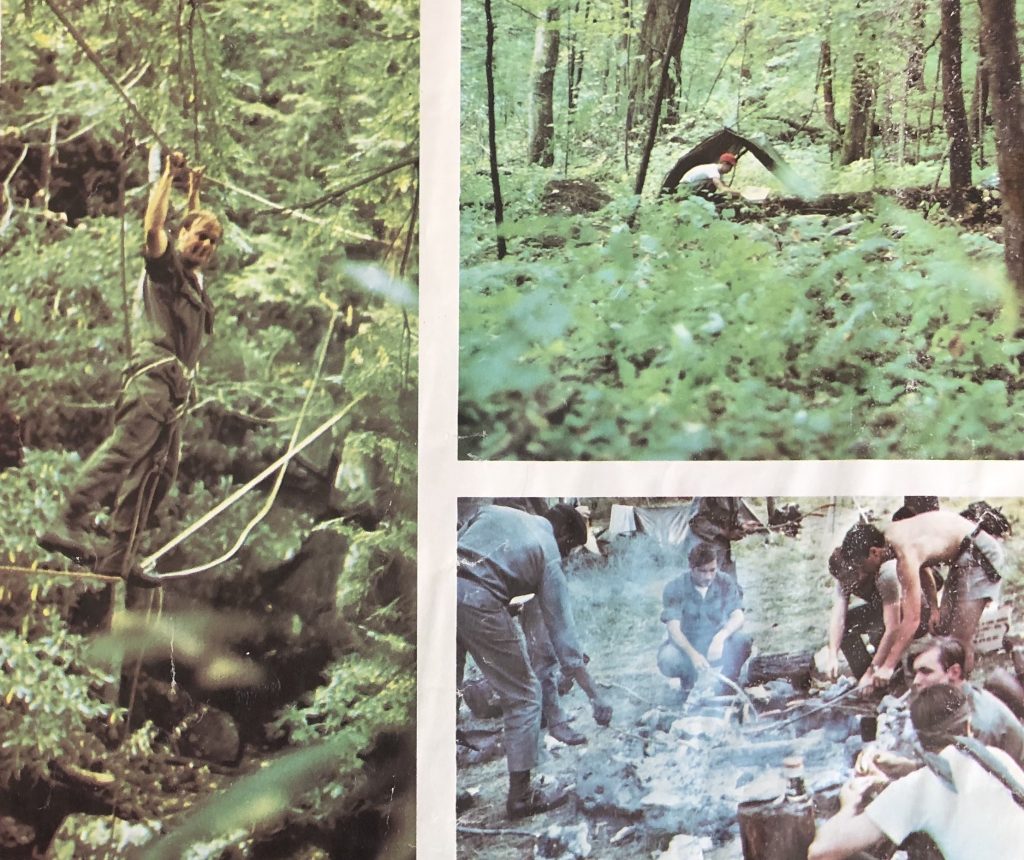

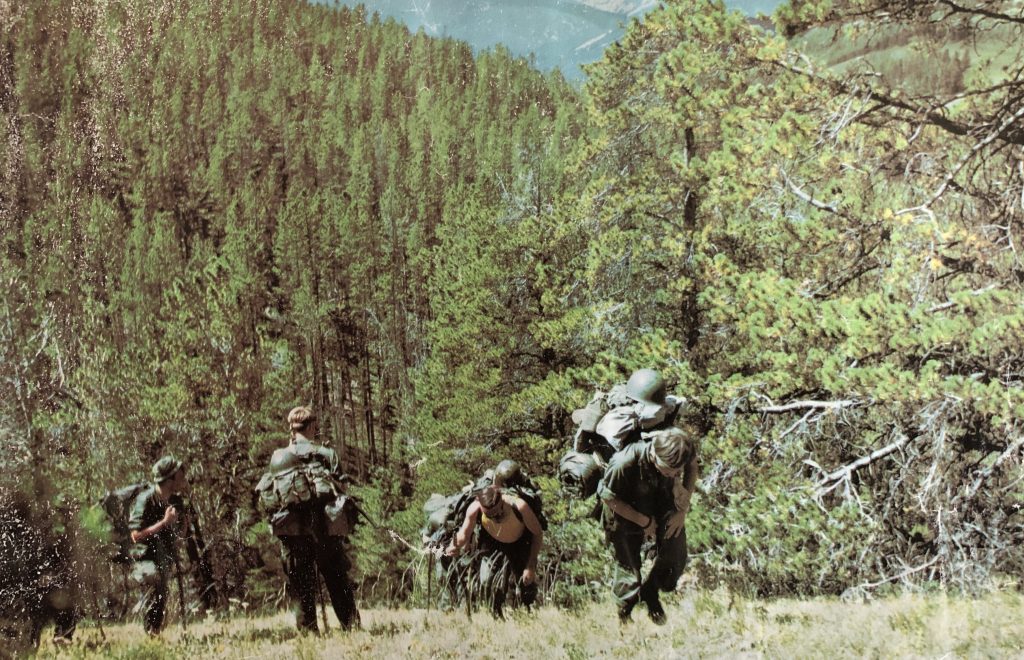

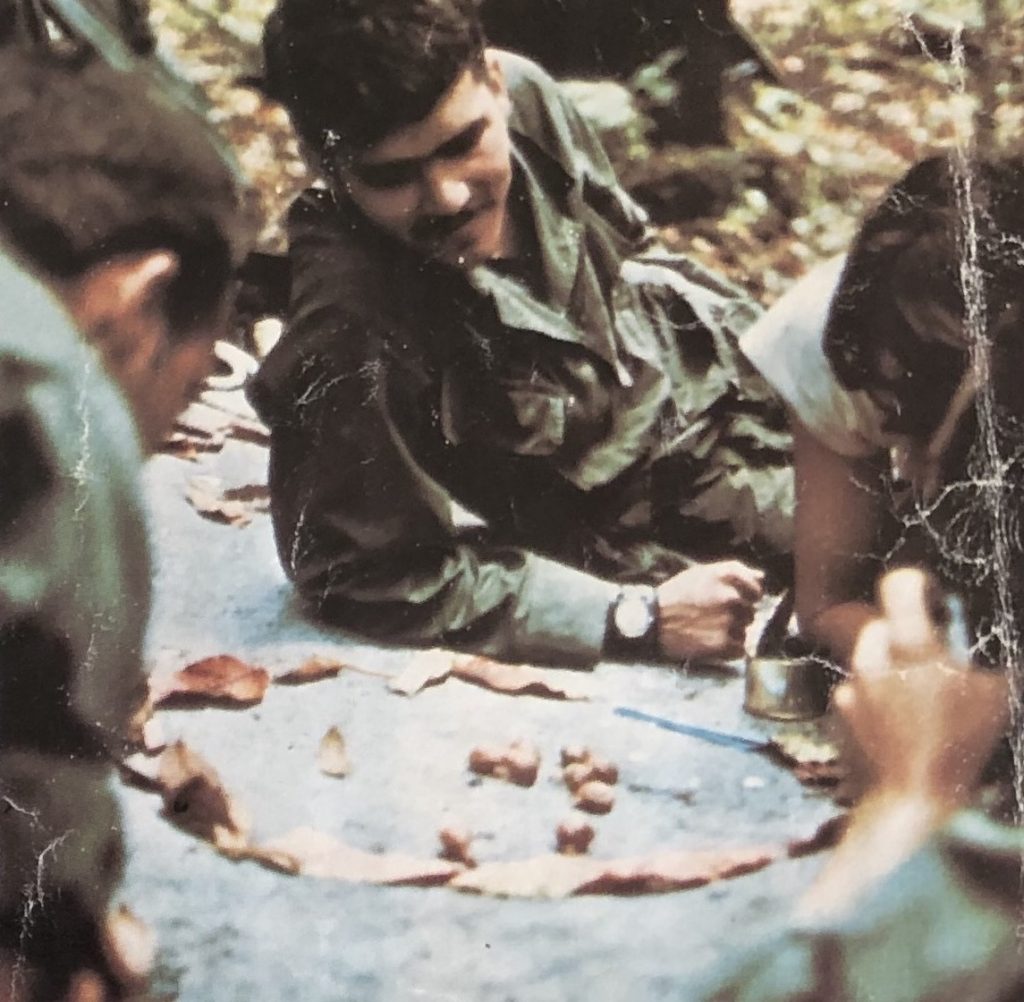

During his tenure in the Army, Robbins helped design and implement an adventure training program for rehabilitating troubled soldiers. He recalls, “There was a compelling need, and the Army realized there was a crisis among its soldiers. Morale was at an all-time low and there was great resistance and hostility throughout the Army. The Spartan Pathfinder program, as it was officially known, was a new and constructive way the Army used to deal with this crisis.” Robbins modeled the training course after his earlier experiences with Outward Bound, creating a 26-day rugged wilderness expedition emphasizing self-reflection, service and a solo – that would meet the group’s reintegration objectives.

Soldiers facing punitive allegations such as drug use, insubordination and disciplinary transgressions, sought restitution by voluntarily joining the Spartan Pathfinder program with the hope of rejoining their units to complete their tours and earn honorable discharges. A special operations unit, known as the Green Berets, directed the Pathfinder program as instructors and mentors. Their special operations skillset proved useful in managing diverse populations, stressful environments, and deescalating resistance and opposition among the crew. Robbins knew that instructors needed to empower their team to contribute and lead. Sergeant Claude Kucinskis, a Green Beret medic said, “We’re not bosses out there to give orders. We’re there to give a helping hand. We try to show we know what we’re doing and what they’ll gain by following us.” Such leadership exemplifies the Outward Bound philosophy of ‘learning by doing.’

Robbins further believed in the power of the natural and untamed environment to rally the group around a singular objective. First Lieutenant Lawrence Michaud, detachment commander for the Spartan Pathfinder program further emphasized that “we’re not bringing stress on the men – the river is. And instead of us bearing down on them, the peer pressure builds up.” Just as Robbins experienced firsthand, a crew that lives and steers the boat together day in and day out, develops a profound fellowship and solidarity that reveals the true potential of collective efforts. The former hierarchy is intentionally removed in order to build equal trust, rapport and reliance among the team. Individuals witness both their singular impact as well as the crew’s combined ability to support, persevere and succeed together.

Aptly imparted on the Spartan soldiers, Robbins pulled from his own journey as a student and crew to envision yet another variation of the Outward Bound School model. The mission of the Spartan Pathfinder embodies the Outward Bound motto, borrowed from the consummate heroic story of Ulysses: Come, my friends, ‘tis not too late to seek a newer world…to serve, to strive and not to yield.